Claim: A summer ice-free Arctic (called by some the “Blue Ocean Event”) will happen within the next few years and will cause an abrupt worsening of climate change and possible runaway feedbacks.

Reality: A summer ice-free Arctic will probably happen within the next few decades, but the exact year will depend on unpredictable natural variability. A summer ice-free Arctic would worsen regional warming and impacts, but would not cause a big or sudden increase in global temperatures.

This is the first post in a new climatetippingpoints.info series fact-checking claims that various climate tipping points have been crossed, and that sudden catastrophic warming is now inevitable. See the Introduction post for an overview.

Some commentators (e.g. 1,2,3,4,5,6) have become worried that the first summer instance of an ice-free Arctic – what some have termed a “Blue Ocean Event” – will happen very soon, and will lead to a rapid increase in global warming and extreme weather through positive feedbacks that could even end in ‘runaway’ warming. In this first post of climatetippingpoint.info‘s new Fact-Check series, we investigate whether these claims add up.

Sea Ice Trending

First let’s take a look at what the Arctic summer sea ice (ASSI) trends are in recent time. In our backgrounder on Arctic feedbacks, we explored how ASSI extent had declined in the last couple of decades, and how this is linked to the ice-albedo feedback. Here’s the data on ASSI extent until 2018:

It’s clear that ASSI is still in decline relative to pre-2007 norms, not only in extent but also in thickness and presence of multi-year ice (the most stable kind), and that this decline is almost entirely caused by human-driven warming. It’s also true that this is happening quicker than the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) originally projected:

People often share this figure to illustrate the glaring mismatch between IPCC model projections and actual observations. But that graph is 10 years old now, and since then models in the more recent IPCC report (AR5) has explored sea ice in some more detail. Although the models are still imperfect, some of them are now in much better agreement with the observed rate of decline (with both models and observations agreeing on ~4 to 5M sq. km for around 2020):

The new round of models (CMIP6) for the upcoming IPCC report (AR6) have reinforced this, with most models becoming effectively summer sea ice-free at around 2oC of warming and the chance of occasional ice-free summers growing above ~1.5oC (see figure below). Based on this, the first ASSI-free year could occur as early as the 2030s and is likely in the 2040s under any scenario, and will become permanent after around 2050 in high emission scenarios:

The decline in sea ice extent in turn has an impact on Arctic albedo, which as explained on climatetippingpoints.info before leads to an increase in regional warming and sea ice melt through an amplifying positive feedback process:

But what about the claim that ASSI will be gone by as soon as 2022? The source of this claim are the trends that can be fitted mathematically to the ASSI volume data, in what some have claimed is “the most important graph in the history of humanity“:

Firstly, it’s worth noting first that this graph is using sea ice volume rather than sea ice area, on the basis that total volume is more linked to climate forcing than extent alone and is declining faster than area, and that thicker ice is more stable. But for feedbacks on climate change we’re mostly interested in extent, as it’s the visible area that reflects back solar energy, and an effectively ice-free Arctic is defined by an extent of less than 1 million square kilometres of sea ice.

The graph above might look convincing enough at first. But one problem with fitting trends like this – and especially non-linear trends like the curved ones here – is that one or two especially low outlying points can drag the trend significantly down, but may well turn out to be anomalously bad years due to inter-year natural variability.

In this case, 2007 and 2012 were especially bad years, where natural variability amplified rather than countered the long-term warming trend. This tendency is shown by how re-fitting these same trends on this up-to-date data delayed the date for an ice-free Arctic by ~5 years when compared with a previous version of this very same graph. And unlike the first ASSI extent graph shown earlier, this graph only uses data from 1997 for it’s straight line rather than the whole dataset, making the straight line fit far less well than the other lines using the whole dataset.

But more importantly, fitted trends assume a predictable underlying pattern that is captured by the simple line you fit. But without understanding the actual underlying physical drivers of this pattern, they can give false confidence in projecting these trends in to the future.

The extent of Arctic sea ice is affected by many factors beyond surface air temperature that make it more difficult to predict, including weather events, cloud patterns, and fluctuating ocean currents, none of which is captured by fitting a simple line. And although the ice-albedo effect is strong, its impact will decline as total ice extent declines. Once sea ice extent is low, a further drop in extent will have less of an impact on regional warming compared to when the extent was higher. As a result, we would expect the decline to begin to slow down once lower extents are reached, and so for the summer ice-free Arctic date to be delayed.

This difficulty in predicting ASSI extent from year to year has led to many predictions of its total collapse that have not come to pass. Back in 2007 some thought that 2013 would first see an ice-free Arctic, a prediction which seemed to be supported by the record low extent in 2012. When 2013 came along and the ice was still above the 2012 record, some predicted 2015 or 2016 instead.

The well-known Arctic researcher Peter Wadhams stated in 2016 in his book Farewell to Ice that, having earlier expected to be gone by the mid-2010s, he now expected an ice-free summer Arctic by 2017 or 2018 – which again hasn’t happened. This repeated postponement has then been used by contrarians to wrongly claim that the wider climate science is flawed.

Now, we are seeing 2022 or later being predicted as the next big year to be worried about for sea ice. But the observed trend is overlain by so much natural variability that predicting a specific year becomes a guessing game that may both prompt excessive alarm and undermine confidence in climate science.

Based on what we’ve seen from both observations and the most recent IPCC report, an ice-free Arctic summer could happen within the next few decades and is likely by around mid-century under medium to high emissions scenarios, but the specific year will depend greatly on natural variability and how much more we emit in future.

An Ice-Free Catastrophe?

What of the second part of the claim we started with, that an ice-free Arctic – the so-called ‘blue ocean event’ mentioned at the beginning of this post – would have catastrophic regional and global climate impacts that risk runaway warming? Here the story has also been overhyped.

Proponents of the ‘blue ocean event’ have proposed four elements for Arctic sea ice loss triggering a jump in temperatures, which has been estimated at 0.5–1.0oC, 0.6-0.9oC, or even 1.6oC above IPCC projections. The main proposed driver of this warming is the ice-albedo effect, meaning that an ice-free Arctic would absorb more heat (as the Arctic Ocean will be mostly blue, as referred to in the “Blue Ocean” name). This in itself true, but the magnitude of global warming because of this has been exaggerated by some.

It has been claimed that Arctic sea ice loss is already significantly boosting global radiative forcing (RF; the actual energy imbalance caused by human emissions since AD1750 that drives global warming, measured in Watts per square metre of the Earth’s surface). Many claims mix and match different units and scales, so for accuracy and understanding below we’ve found the appropriate RF value and then estimate 21st century temperature impact using a transient climate response of +~1.9oC per doubling of CO₂ [0.51oC per W/m²] (relevant over a few decades, versus a climate sensitivity of +~3oC per 2xCO₂ for a timescale of centuries). For example, the current total change in RF due to human activity is +2.3 W/m², which translates to a near-term warming of ~1.2oC.

It’s been suggested that sea ice loss in the Arctic is already having the same effect as one quarter of all the CO₂ released since 1979 as a result of the ice albedo effect. The source of this number calculated that the increase in RF from melting sea ice is equivalent to 25% of the warming caused by CO₂ alone from 1979 to 2011 or 2016 (based on an RF increase of ~0.2 W/m² from ASSI loss, which would lead to ~0.11oC of warming, and 0.8 W/m² from CO₂ – see below for more on this).

Other model-based estimates and emergent constraints for current forcing from ASSI loss tend to be a bit lower at ~0.1 W/m² from 1979-2007 (equal to +~0.05oC) or 0.11-0.15 W/m² per degree of warming, although the large drops in ASSI since 2007 likely accounts for some of the difference by 2016. There is also uncertainty over how much cloud feedbacks might interact with ASSI loss, with some arguing that negative cloud feedbacks elsewhere will counteract Arctic changes, while others predicting a probably negligible or maybe even a positive feedback from clouds.

For a totally ice-free Arctic summer it has been claimed that global temperatures would quickly go up by between 0.5oC and 1.0oC. This is linked to comments made by Peter Wadhams in his book Farewell to Ice, where he says that a summer ice-free Arctic would increase radiative forcing by 50% of total historic carbon emissions. Given that the RF from CO₂ emissions so far is ~+1.6 W/m², this would imply an RF increase of ~+0.8 W/m² (about +0.4oC in the near-term & ~0.6oC by 2100).

However, estimates in peer-reviewed scientific papers of the global RF increase for a consistently summer ice-free Arctic (which becomes likely by the time global warming reaches around +2oC) are much more modest at around +0.3 W/m², which would lead to near-term warming of about 0.15oC (and ~0.25oC by 2100).

The initial estimate for summer ice-free Arctic above is actually closer to the estimate for a year-round ice-free Arctic* (+RF ~0.6 to 0.7 W/m², or about +0.35-0.55oC, assuming negligible cloud feedbacks), which isn’t expected until at least the 22nd Century. There’s also no evidence that the increase in radiative forcing from albedo would come as an abrupt jump rather than scaling up gradually proportional with sea ice loss, with half this warming having already occurred.

[*A potential source of this mismatch is that the original source Wadhams cites for +25% of CO₂ warming so far – which is then doubled for future melt – used a lower figure for historic CO₂ RF of 0.8W/m² for its RF comparison. Half of this is 0.4W/m² & 0.2-0.3oC for ASSI loss, which fits with other literature estimates but is smaller than what is often publicly suggested. Some estimates appear to instead mistakenly use the higher CO₂ RF estimate of +1.6 W/m² from the IPCC (or even all of the +2.3 W/m² of RF so far) to calculate the 50% relative increase, but this doesn’t match the numbers used in original source for this comparison. To keep things consistent, we directly use the actual RF estimates (~0.2W/m² for ASSI loss so far & 0.3-0.4W/m² for total ASSI loss) from the original source that Wadhams and others cite.]

This means a summer ice-free Arctic – which we would expect within the next few decades unless aggressive emissions reductions are pursued in the next decade or so – will add ~0.15-0.2oC (of which around half has already happened) to global warming earlier than expected in earlier reports, and although small this makes it that much more difficult to limit warming beyond 2oC.

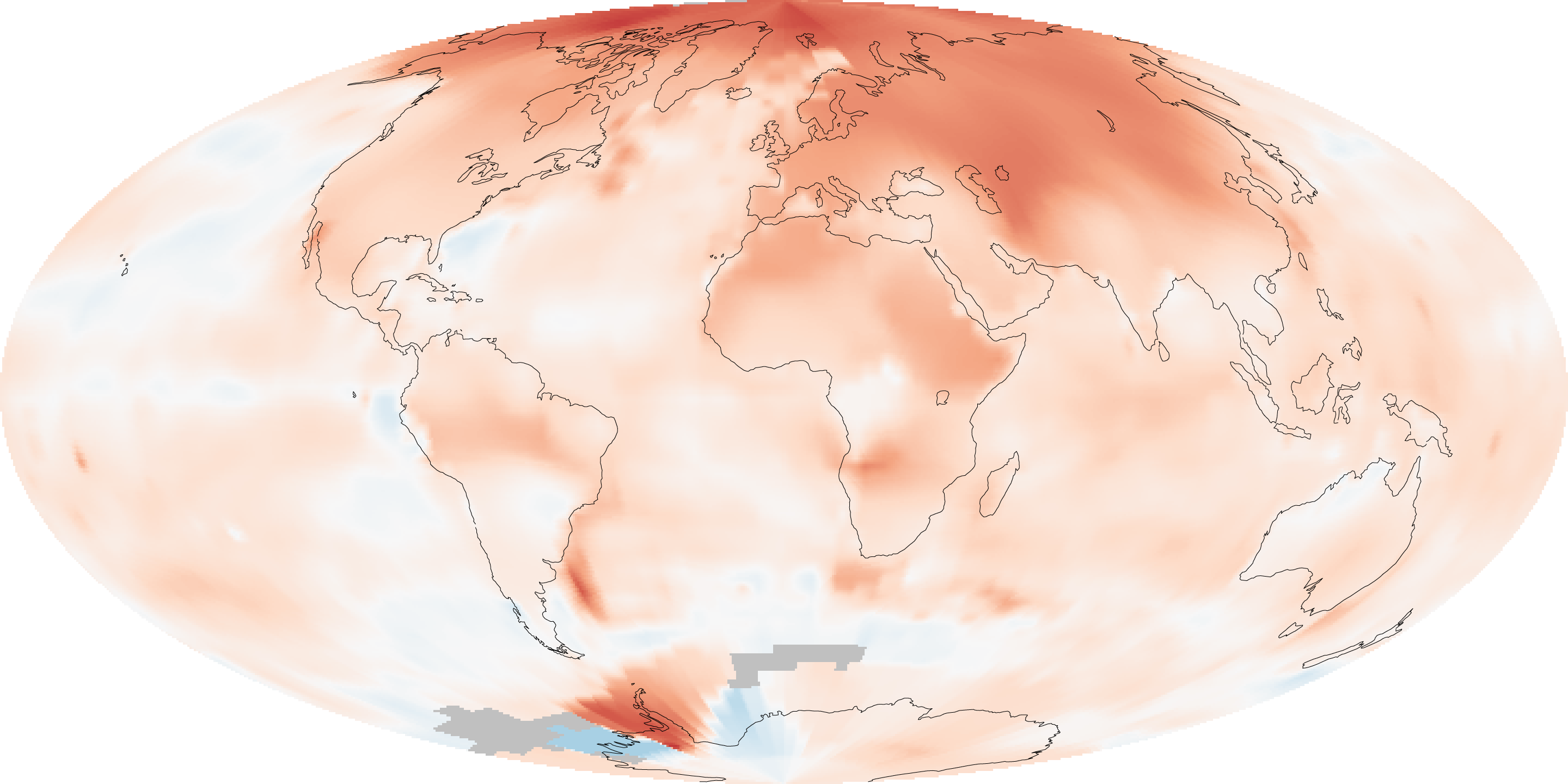

This additional warming will be mostly concentrated in the Arctic and most keenly felt regionally rather than globally, contributing to the already observed “Arctic amplification” of global warming. The Arctic has already warmed up over twice as much as the global average, which as well as helping to melt sea ice is also affecting ice on Greenland and the permafrost and Boreal forests surrounding the Arctic Ocean:

This amplified Arctic warming could in turn affect the Northern Polar Jet Stream, a “river” of fast-moving wind high up in the troposphere (the bottom layer of Earth’s atmosphere) which dictates much of the Northern Hemisphere’s broader weather.

A strong, stable jet stream relies on a large temperature difference between the equator and the pole. Now that the Arctic is warming up faster than the lower latitudes, that temperature difference is reducing and the jet stream is getting weaker. This may be making it easier for large air masses to ‘push’ the jet stream out of place, making it meander and sometimes split.

This means warm air masses can end up farther north than usual and vice versa- recent cold and warm weather extremes in North America and Europe might be linked to the Jet Stream weakening. Reduced ASSI might also be affecting the North Atlantic Oscillation, a multi-year air pressure pattern affecting weather in Europe and North America.

Another way that warming could lead to weather extremes in the mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere is the “polar vortex”. The stratospheric polar vortex is a region of air about 50 km high contained by another, polar, jet stream, known as the polar night jet (so-called as it only exists during the dark polar winter).

When the stratospheric polar vortex weakens it can trigger a sudden stratospheric warming and allow cold Arctic air to move south. Although these happen naturally over the last 37 years they have become more common, and some have suggested low sea ice in key areas might help trigger them.

If these links are significant, the fear is that these weather extremes could get worse in future and affect human health and crop yields in the Northern Hemisphere. But some proponents of the ‘blue ocean event’ scenario have recently argued that these weather extremes would have devastating impacts, with abrupt Arctic warming triggering the weakening or even loss of the Jet Stream, total crop failure, and societal collapse within only a few years.

However, the science has not yet been definitively settled on the extent to which Arctic sea ice and northern hemisphere weather extremes might be linked, and it’s too early to tell how strong the trend in Arctic-driven weather extremes currently is or will become. Claims of a radical Jet Stream weakening also rely on huge temperature jumps when summer sea ice is lost, which as discussed above is unlikely to be so dramatic.

Latent Feedback

The second proposed element of the ‘blue ocean event’ scenario is the ‘latent heat’ feedback. When heat (thermal energy) is applied to ice, the temperature of the ice increases. When the ice starts melting as energy continues to be applied, the ice’s temperature remains the same until it has converted to water. This energy that is absorbed to change the structure of the material rather than its temperature is called latent heat. Conversely, the freezing of water to ice releases heat.

This means that the net melting of Arctic sea ice slightly reduces global warming (as measured in surface air temperature), as the melting ice absorbs a bit of the ocean or atmosphere’s heat instead. Conversely, once sea ice has disappeared this would mean that less heat is used by melting ice, so more heat might remain in the ocean or atmosphere instead.

The proportion of anthropogenic heat that has gone into Arctic sea ice so far is only around a third of what has gone into the atmosphere (around 0.3oC of equivalent atmospheric warming) though, and tiny versus what’s gone into the ocean:

Some discussions of the latent heat feedback implicitly focus on the summer sea ice (sometimes interchanging it for all sea ice) and ignore that every winter the sea ice re-forms again, continuing the cycle of latent heat absorption and release even if summer sea ice reaches zero. This ice melt heat sink would only be entirely lost if all sea ice disappeared forever, but all of the trends we have been looking at are specifically for summer sea ice – no model or observations supports the total loss of winter sea ice this century, even after losing summer sea ice at some point.

This means that although there will be an increase* in the rate of heat accumulation in the ocean and atmosphere due to sea ice decline, it will be very small compared to the overall global heat balance [*the exact rate is hard to predict, as heat budget measurements have mostly focused on the dominant ocean].

It’s also important to note that this latent heat is not hidden away in the sea ice and so will not suddenly be released and cause and abrupt atmospheric temperature rise once the ice melts – the heat was absorbed by the melting ice to change its state and is effectively permanently stored in the liquid water.

On top of that, increasing evaporation from the warming oceans (including from the newly opened ice-free Arctic) also uses far more latent heat worldwide than just sea ice, further complicating how much latent heat fluxes will change both in the Arctic and globally in future.

Overall, with Arctic sea ice latent heat we have a globally-small heat sink getting smaller over time as the volume of sea ice melting each summer declines, relative to a far larger ocean heat sink and increases in the global latent heat flux due to evaporation from warmer waters. We do not have a sudden release of ‘hidden’ heat back into the atmosphere, as implied by some presentations of a catastrophic ‘blue ocean event’ scenario.

Arctic Feedbacks on Runaway Rhetoric

The final elements for the hypothesised catastrophic impacts of a ‘blue ocean event’ are the release of methane from both methane hydrates under the seabed and from permafrost on land – known by some as the “Arctic Methane Bomb”.

The issue of potential tipping points involving Arctic methane is a complex one which we explore in greater detail in this separate in-depth Fact-Check. But as a brief summary, the evidence for imminent and dramatic release of methane from the Arctic is very limited, and a longer-term, non-catastrophic leakage of methane is far more likely.

Further evidence for non-catastrophic impacts of an ice-free Arctic come from several thousand years ago in the early Holocene (shortly after the end of the last Ice Age glacial), a time of a relatively stable mild climate with no evidence of abrupt warming despite palaeo evidence of a period of relative regional warmth and ice-free summers in the Arctic Ocean.

Finally, an Arctic sea ice tipping point doesn’t mean that the Arctic becoming ice-free will cause a sudden and dramatic global warming event. A common misconception with tipping points is that they’re always abrupt, dramatic events, when in reality their most important feature is their self-perpetuation even if they then only happen gradually.

In this case, the tipping point would be when losing summer sea ice would become inevitable through elevated regional warming even if human emissions ceased. The latest IPCC reports suggest that for a low emissions scenario there’s still a chance that some summer sea ice could survive, although continued emissions make this unlikely. The latest report (AR6) also makes it clear that ASSI doesn’t appear to have a clear tipping threshold, unlike Arctic winter sea ice.

Summary

Together, observations, theory, modelling, and palaeorecords suggest that a summer ice-free Arctic is not yet imminent, and will not trigger a globally catastrophic “Blue Ocean Event” when it does.

The first ice-free summer in the Arctic will happen sooner than originally thought and likely sometime in the next few decades, but is hard to predict exactly when because of large natural variability on top of the human-driven warming trend.

And while losing the summer sea ice will drive significant regional warming and and may increase mid-latitude weather extremes, the global warming boost will be modest (estimated at +~0.15-0.2oC, of which around half has already happened) and won’t happen in one sudden jump.

As with many climate tipping points, an ice-free Arctic won’t be the trigger for an abrupt, dramatic event. It is rather an unwelcome extra amplification of climate change that will have an impact over many decades.

Climate tipping points will likely make climate change worse than expected and more difficult to counter, but claims of a near-inevitable chain reaction to runaway warming as a result of an ice-free Arctic are wide of the mark.

~

This post was written by Dr. David A. McKay, currently a Postdoctoral Researcher at Stockholm Resilience Centre (Stockholm University), where he is part of the Earth Resilience in the Anthropocene Project (funded by the European Research Council) and is researching non-linear climate-biosphere feedbacks. This post was written in his spare time with no funding support for this site, and was proofread and edited by Dr. Rachael Avery.

Updated: 26/4/19 with a link to a new paper which supports the summer/winter ice-free Arctic RF estimates and a recent paper with probabilities of an ice-free Summer relative to the level of global warming. 30/7/19 with updated references for radiative forcing from ASSI loss so far, additional support for an RF of ~0.7 W/m2 for total ASSI loss (but with large uncertainty from cloud feedbacks), and some figure rounding. 15/11/19 with a new emergent constraints study that supports current ASSI-free RF estimates and mid-century timeline, plus new subheading links to allow direct linking to sections; 12/6/20 clarified TCS value used here and a source provided; 6/7/20 with new CMIP6 sea ice projections; 24/8/20 with new note exploring the potential source of the mismatch between Prof. Wadham’s and other papers’ ASSI-loss warming estimates; 30/10/20 with clarification on long-term ASSI warming & estimate mismatches; 17/11/20 with new article on ASSI-jet stream link; 23/11/21 minor reformatting & updated ASSI decline chart.

https://www.pnas.org/content/111/21/E2159 Recently found this paper: Reply to Legates et al.: Negligible role of arctic cloud albedo changes in observed darkening.

Does it change anything relevant within this article?

LikeLike

Hi Lancton, thanks for the link. I’m aware of this exchange, and it does seem to be mostly a disagreement over spin and semantics. I think the overall assertions that arctic sea ice albedo loss has a big regional impact with a reasonable global impact (of ~0.2 Wm^-2) [the original Pistone et al paper] but that this doesn’t include counteracting global negative cloud feedbacks (reducing the global impact to more like ~0.1 Wm^-2, in line with independent observations) [the Legates et al reply] are not mutually incompatible – in effect both papers are right, it’s just their spin is different.

I’m also aware that the same team have new similar paper out (https://scripps.ucsd.edu/news/research-highlight-loss-arctics-reflective-sea-ice-will-advance-global-warming-25-years) which also might seem to imply that my sums underestimate arctic/global warming form sea ice loss, but actually the details line up fairly well too (i.e. ~0.7Wm^-2 from *all* sea ice loss, and that their estimates are again provided without cloud feedbacks which would likely counteract up to half of it). I think it’s one of those things that sometimes scientists can seem like they’re massively disagreeing over an issue, when in actual fact they mostly agree and are just emphasising different aspects!

LikeLike

Hey David, thanks for hosting this site. It’s brought some logic- and science-based calm to my overly-anxious brain after slogging through r/collapse far more than I’d care to admit but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t still skeptical about how much time we have and that everything happening now doesn’t frighten me deeply. The fires in Russia and the rest of the arctic that are getting worse with no end in sight, the fact Alaska’s sea ice has totally melted away (updated ~17 hours ago: https://mashable.com/article/alaska-sea-ice-melt-2019/), Greenland is melting in far greater amounts and faster than expected (EVERYTHING seems to be happening “faster than expected”)…do any of these recent events change anything about your predictions and mindset about how things are “progressing” overall regarding climate collapse and where we actually are in the timeline?

LikeLike

Hi, thanks for the positive feedback! It’s understandable to be worried by all the current climate news, and certainly none of the recent observations are good and some (but not all) of it is happening faster than expected. But quite often these things are spun as evidence of imminent runaway warming, when most of it is actually not far off current projections. A lot of it has to do with the upward creep of extreme events on top of the underlying warming trend.

For example, Greenland has indeed recently reached melting rates expected until ~2070 (e.g. https://twitter.com/xavierfettweis/status/1156487868950482945), *but* with the key (and under-reported) details that this year’s melt was an extreme outlier event lasting for a few days which just about reached the projected *average* 2070 meltrate for the *whole month*. When the July average meltrate is calculated it will be lower than the ~2070 projected average, so it’s not accurate to say the Greenland ice sheet is literally melting at the 2070 rate already, just that it briefly hit that level for a few days only. This is because large climate and weather variability means that we’ll hit these temporary extremes sooner than the long-term average trend gets there (in the same way that the recent european heatwave is only a foretaste of that being average conditions by late-century, and not that warming arriving ~50 years early). A similar case also applies to the permafrost melting 70 years early meme, which I did a twitter thread on a little while back (tl;dr is that only one type of many is melting faster and not rich in carbon, plus the 70 years timeframe is scenario-choice-dependent – to me it looks more like 30 years): https://twitter.com/ClimateTipPoint/status/1141279000473559040

For the Arctic sea-ice, the Alaska meltback is indeed worrying but unfortunately not unexpected – as with the above we’ll continue to see new records repeatedly broken in warm years like this (but with the caveat that climate variability means some years & decades will warm faster than others, so drawing a trend out needs care), so I think the Arctic sea-ice post’s projections still stand. Of course I’ll update it if things change though! The Siberian boreal forest fires are also bad, but alas also not unexpected (how it might affect permafrost feedbacks is an open question, which I recently discussed in the comments on the committed warming post).

I guess my overall message here would be that even a warming of only 1.1 degrees celsius has already shifted the probability of climate extremes up dramatically resulting in lots of records being repeatedly broken, but that doesn’t make each extreme event the opening act of a climate tipping point or runaway warming in action. Some things are happening faster than expected (e.g. sea-ice vs. older sea-ice models, *but* these are now getting much better: https://twitter.com/RDavy84/status/1157302796791820288), but events like the July 2019 Greenland melt are more a case of extremes shifting upwards and setting new records in the process. Given this is all happening at 1.1 degrees it just goes to show why avoiding 1.5-2+ degrees is so important! And as a I put elsewhere: climate change is already serious enough to justify radical and immediate action without having to invoke apocalyptic tipping points – all these recent events are just the further unfortunate proof of just how serious the situation already is.

LikeLike

Hi David – Really nice post, thank you for putting it together. I would love to see an expansion on latent heat and summer ocean temperatures. My personal concern from various readings is that the presence of any summer sea ice effectively keeps the surrounding waters nears 0C. Once it is gone, even temporarily, the ocean temps can spring upwards.

So while the Arctic will continue to refreeze in the winter for a long time to come we might start to see a spike above and beyond existing trend lines in Arctic temps in the summers in the absence of SSI. I guess I see the summer ice as a bit of a force field – it works up until it doesn’t. With a spike — even temporarily — in Arctic temps the jet stream is compromised (even more) and can allow the intrusion of huge quantities of heat.

To throw in another metaphor, once the yearly plots of summer Arctic temps start regularly going above 0C it’s like the proverbial camel nose entering the tent – it will obstinately push forward.

LikeLike

Hey bostonblorp, thanks for the positive feedback!

So with the arctic seaice latent heat, there would indeed be an increase in heat accumulation in the rest of the ocean-atmosphere system during ice-free months (as heat that would have gone into melting ice instead of increasing temperatures goes elsewhere), but they key point to remember is that heat absorption by melting seaice remains a relatively small heat sink on a global scale (https://climatetippingpoints.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/global_warming_components.gif) and some of the heat accumulation increase will also continue to be offset by the subsequent seasonal melting of returning winter seaice (giving a smaller net heat accumulation increase).

Furthermore, seaice acts as very efficient insulating cap to the Arctic ocean below (https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/SeaIce), and so newly opened Arctic ocean water will start to release heat, which is likely a much bigger effect than the latent heat effect and is already at work now with the rapid loss of thicker multi-year ice. The open water will also begin to evaporate even at low temperatures, which like melting ice also requires lots of latent heat to do, and so effectively evaporation will act as a heat sink much like seaice melting was. It’s also worth reiterating here that once heat goes into melting ice as latent heat it’s not stored for re-release when melting is complete – that energy remains effectively sequestered in the new liquid structure until it freezes again.

The overall picture then is one of summer seaice melt being one of very many and complex global heat sinks, with others (deep ocean heat storage, surface evaporation, etc) being bigger and regional changes in heat fluxes partially modulating the loss of the seaice heat sink. There would be an increase in heat accumulation in seaice-free summers as you suggest, but to trigger a sudden temperature jump all of this heat would have to go straight to the atmosphere above and not to the far bigger ocean heat sink below. My bet would be that at least some if not most of this extra heat would go in to the ocean (from seaice no longer melting from below, allowing more heat to accumulate in that water), acting as a small but not significant feedback on the global temperature increase through an increase in global ocean heat storage (& so slightly reducing capacity to absorb atmospheric warming).

There’s no doubt though that a seaice-free summer would be much warmer, not just from whatever pushed that year to be particularly warm in the first place but due to the reduced albedo, increased ocean heat loss to Arctic atmosphere, and a bit from the latent heat effect too. But all of these processes act on a continuum scaling up fairly linearly with seaice reduction, so although losing all seaice would see the maximum impact of all these heat sink losses / heat source gains it wouldn’t mark the point of a big sudden heat release. Although seaice melt may well feature a tipping point (beyond which total loss is guaranteed), my current analysis is that there’s no clear tipping point in direct warming due to seaice loss itself – it remains a quasi-linear positive feedback scaling with seaice extent and with no threshold triggering an abrupt jump.

This is also why I think a sudden jetstream disruption is unlikely, as the temperature feedback from seaice loss would scale up fairly smoothly (subject to natural interannual variability). It’s also worth reiterating that the seaice-jetstream link is still being scientifically debated, with at least one recent paper finding that they might be correlated by being driven by the same cause instead: https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/08/arctic-sea-ice-loss-isnt-to-blame-for-your-cold-winters/

Hope that helps to clarify!

LikeLike

Hello! Very good article, you explained it really well and very clear. In fact, this whole blog is really helpful, and I know it must be hard to keep up with updates and all, but the explanations are really good and the fact-check seems pretty on point. So congrats on that!

However, while reading this post, I got some doubts, and I was wondering if you could answer some of them.

For example, about the loss of ASSI boosting warming for about 0.15-0.2°C. Is it referring to the amount of warming that will happen in the already-warming Arctic local zones, meaning that it will rise the rate of warming restricted to that area by that amount? Or does it mean then that global temperatures will rise by 0.15-0.2°C instead?

Another question: you mention that warming will be gradual rather than an abrupt jump. Does it mean that, once ASSI is gone, the temperature will rise gradually by 0.15-0.2°C during the following years, rather than temperatures immediately jumping by that amount the same or the very next year? Or does it mean instead that, since you mention that about half of it has already happened, by the time ASSI is gone temperatures will have already gradually risen by 0.15-0.2°C?

And this brings me to the last question (and I apologise if it sounds a bit silly): by every year that ASSI is lost (since it grows back in winter) does it mean that temperatures will cummulatively rise by 0.15-0.2°C by each year of lost ice in summer? I know this seems to contradict my earlier questions and sounds a bit silly, but I wanted to be sure nonetheless.

So, to sum up, would the 0.15-0.2°C figure be the amount of maximum warming that ASSI loss could add by the end of the century? And I’m sorry for making so many questions, I know you must be busy, but I hope you can answer these questions!

Keep up the good work & take care!

LikeLike

Thanks Ann! Re. your questions, the 0.15-0.2C is the global figure – the local warming is much more (combined factors have made the Arctic warm twice as much as the global average so far). And for the next Q, it’s the latter case – around half of this extra global warming has already happened (assuming negligible cloud feedbacks), and by the time ASSI is totally gone we will reach ~0.2C extra global warmth. I’m not sure I quite get the final Q, but the extra ~0.2C is the global average of the cumulative increase due to the change in radiative forcing from reduced albedo, and is occurring over decades rather just within each summer. Hope that answers your questions!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the explanation! And yeah, that was what I meant with the last question, so I apologise if there was any confusion.

One last thing (sorry, I thought about it after sending the last comment); if I’m not wrong, models already take into account warming caused by sea ice decline (or at least, some of it), right? I don’t remember where I read that, I think it was on another post on this blog, but I don’t rembember in which one exactly, or if I read it somewhere else.

I hope you don’t mind answering that, I promise this is the last question! Thank you so much again!

LikeLike

Yep, models do indeed already take account of warming from sea ice decline, but in AR5 (the last big IPCC report) only a few models managed to match the speed of ASSI decline (see panel b, where dotted lines are the average of all the 29-37 model projections for ASSI, and solid lines the 3-5 models that have a better physical representation: http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/figures/WGI_AR5_FigSPM-7.jpg). So although models already have this ASSI-decline warming in them we’re likely to see it sooner than they expected, and so in the meantime it effectively acts a temporary extra warming boost (although as discussed it’s still relatively small on a global scale). In this regard Arctic sea-ice decline is not so much a classic tipping point (with extra warming either committed to or not), but an expected positive feedback with an uncertain timescale.

LikeLike

Hi David,

I agree with most of your conclusions in this post, but I have a question about this: “although the ice-albedo effect is strong, its impact will decline as total ice extent declines. Once sea ice extent is low, a further drop in extent will have less of an impact on regional warming compared to when the extent was higher. As a result, we would expect the decline to begin to slow down once lower extents are reached, and so for the summer ice-free Arctic date to be delayed.”

Is that final clause suggesting that “the September ice-free Arctic date [will] be delayed”?

Thanks,

Ben

LikeLike

Hi Ben, that’s indeed what I mean. The difference can be seen in the contrast between this plot used in XR’s early talks (https://climatetippingpoints.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/image7.png) in which in most fitted-curves the ice loss keeps accelerating until it hits zero, versus this plot from the most recent models (https://climatetippingpoints.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/grl60504-fig-0002-m.jpg?w=1024) in which after initially accelerating to the rapid drop we observe the ice loss starts to decelerate as it approaches ice-free conditions. This makes the loss more like a logistic/sigmoid than an exponential curve (like the inverse of these: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/1223/2017/02/10222207/Figure_45_03_01.jpg) – in general many natural phenomena are better fit by logistic curves, but before their mid-point it can look just like exponential.

LikeLike