This autumn, several media articles reported on a study showing the global carbon sink on land – which so far has drawn down around a quarter of human carbon dioxide emissions – took up very little carbon in 2023. This inspired headlines that the Earth’s natural carbon sinks are failing or have “collapsed“, with potentially dire consequences, and follows on from concerns that the Earth’s “buffering capacity” to emissions have already been showing strain in both land and ocean carbon sinks.

In this post, we’ll take a look at the claims of carbon sink collapse, and put them in context of the latest research on the state and future of the carbon cycle.

Sinking in

Carbon dioxide has been steadily building up in the Earth’s atmosphere, as shown by the famous ‘Keeling Curve‘ measured at Mauna Loa.

The main driver of this increase is fossil fuel burning and industry (around 89%), as well as land use change like deforestation (around 11%), which added up to around 42 billion tones of CO₂ emissions in 2024. However, not all of the CO₂ emitted stays up in the atmosphere. So far over half has been reabsorbed by so-called ‘carbon sinks’, with around 33% of emissions being taken up by plants and stored on land (the ‘land sink’) and 25% dissolving in to seawater (the ‘ocean sink’).

This means only 42% of the CO₂ emitted by people so far has actually stayed in the atmosphere. Without this natural CO₂ drawdown then there would be around twice as much CO₂ in the atmosphere, meaning we’d be facing much more warming if it weren’t for natural carbon sinks.

Recently though concerns have been raised that “We’re seeing cracks in the resilience of the Earth’s systems… terrestrial ecosystems are losing their carbon store and carbon uptake capacity“, leading to the “buffering capacity” provided by land and ocean sinks starting to reach its limits.

In particular, one recent study heavily covered by the media found that the land sink drew down much less carbon in 2023 than normal, leading to headlines and commentary [e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] suggesting that Earth’s carbon sinks have “collapsed“, implying a permanent reduction. Does this mean that Earth’s natural carbon sinks won’t take up CO₂ any more, leaving far more in the atmosphere and so accelerating warming?

Keeping steady

To understand the significance of what happened to the land carbon sink in 2023, we need to look at some numbers and put them in wider context.

Firstly, the decline in the original study triggering the recent stories was specifically in the land sink, and not the ocean sink. In fact, the study on 2023 found that the ocean sink actually had a good year in 2023, increasing by ~0.1 billion tonnes of carbon (GtC), i.e. an extra 4% or so compared to 2022, due to the effects of El Niño on CO₂ emissions from the Pacific Ocean. This means that claims or implications that all of Earth’s carbon sinks declined or collapsed in 2023 are wide of the mark.

Secondly, while large the land sink drop was not a total collapse. The study on 2023 found the combined sum of land use emissions plus the land sink (i.e., the ‘net atmosphere-to-land flux’) was a drawdown of circa only 0.4 GtC last year, compared with an average of ~2.1 GtC a year over the past decade. However, the most recent Global Carbon Budget – considered to be the authoritative annual update on the carbon cycle’s status, and featuring more models – estimated a smaller atmosphere-to-land net flux drop in 2023 to ~1.1 GtC (of which, just the land sink was ~2.3 GtC, versus the past decade average of ~3.2 GtC per year), suggesting a more modest drop. Together with the stable ocean sink, this is not the total global carbon sink collapse implied by some.

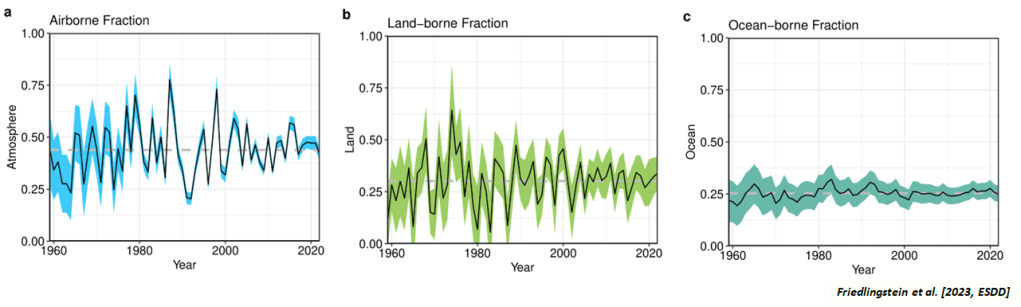

Thirdly, and most importantly, past records suggest that the sort of land sink drop we saw in 2023 was not so unusual, and that the long term trend is stubbornly stable. These graphs below show the fraction of CO₂ emissions staying in the atmosphere or going into the land & ocean carbon sinks:

In each ‘fraction’, and particularly for the airborne and land fractions, there’s a lot of variability between different years (referred to as ‘inter-annual variability’), with many previous years seeing very low land sink values (e.g. in 1979 or 1986). Some of these are associated with El Niño years, which typically see drying over several tropical regions and therefore low CO₂ uptake in key carbon sinks (and high airborne fractions in turn), while La Niña years often see higher CO₂ uptake.

In this context, 2023’s land sink drop, which the study shows is directly linked to 2023’s strong El Niño and the droughts and heat extremes it produced, is so far not an outlier. It can also be seen that previous drops were all temporary, reverting back to the long-term trend of remarkably stable sink uptake.

Of course it’s possible that the global land sink will fail to recover to the long-term stable trend this time round, and 2024’s record warmth and continuing drought and wildfires may not help. However, provisional results from the Global Carbon Budget 2024 projected that the land sink recovered in 2024, matching the default expectation for the land sink to recover now that the recent El Niño has receded.

There is some evidence though that some land sinks are struggling, as recently highlighted by Johan Rockström in this TED talk. For example, we know that tropical forests peaked as a carbon sink in the 1990s, particularly driven by the Amazon (which satellites suggest is losing resilience, and including land use change is now a net carbon source), while the boreal forest sink is also declining due to increased wildfires, beetle outbreaks, and logging.

Despite these regional declines, as shown by the graphs above the global land sink fraction has remained steady over recent decades. This is because declining CO₂ uptake by intact tropical and boreal forests has been balanced out by increased CO₂ uptake in regrowing forests in the tropics, as well as in some existing forests in China for example.

As a result, at the global scale the land sink has remained steady, and would require far more widespread losses or a reversal of regrowth sinks to start declining. Whether this happens soon depends on how much the record warmth of 2023-24 is part of inter-annual variability on top of long-term warming, or a more substantial shift in the climate system.

Hitting the buffers

Putting 2023’s land sink drop in context then shows that while a bad year it’s likely not unusual, and the long-term trend is of a stable sink at the global scale, with declining sinks balanced by increasing ones at the regional scale. The next question then is how long can we expect this to continue, and could 2023 be the start of a change in the long-term trend?

First off, we can look at what would happen to carbon sinks if emissions stopped now. This is of course very unlikely, but it gives us a good idea of the current state of carbon sinks. To do this we can look at model results from ZECMIP (the ‘Zero Emission Commitment Model Intercomparison Project’), which estimated how much warming may be “locked in” from emissions so far by stopping emissions abruptly in Earth system models to see what happens.

Unlike earlier expectations of lots of lagged warming from the effect of ocean heat storage, these simulations found on average no extra warming once emissions stopped (as discussed in an earlier climatetippingpoints.info post). This is because, unlike the earlier estimates assuming CO₂ levels stayed fixed, in more realistic Earth system models CO₂ starts to fall as a result of natural carbon sinks continuing to draw down carbon even after emissions stop. The cooling this causes roughly balances out the lagged warming from the ocean, resulting in today’s expectation of warming stopping not long after emissions reach net zero.

There is a lot of variation between these models though – some see cooling of around 0.3°C after net zero, while others see up to 0.3°C warming. The differences are driven by how much warmth the ocean takes up and re-releases in each model, as well as how strong their ocean and land carbon sinks are, with ones with weaker sinks tending to see some warming after net-zero.

There’s some observational evidence that land carbon sinks may be weakening faster than projected by most models, and the 2024 Global Carbon Budget estimates that the ocean and land sinks were 6 and 27% smaller this decade than they would have been without climate change. A precautionary approach then would be to assume that models on average may be over-estimating future carbon sink capacity and under-estimating post-net zero warming, which would put the onus on cutting emissions faster.

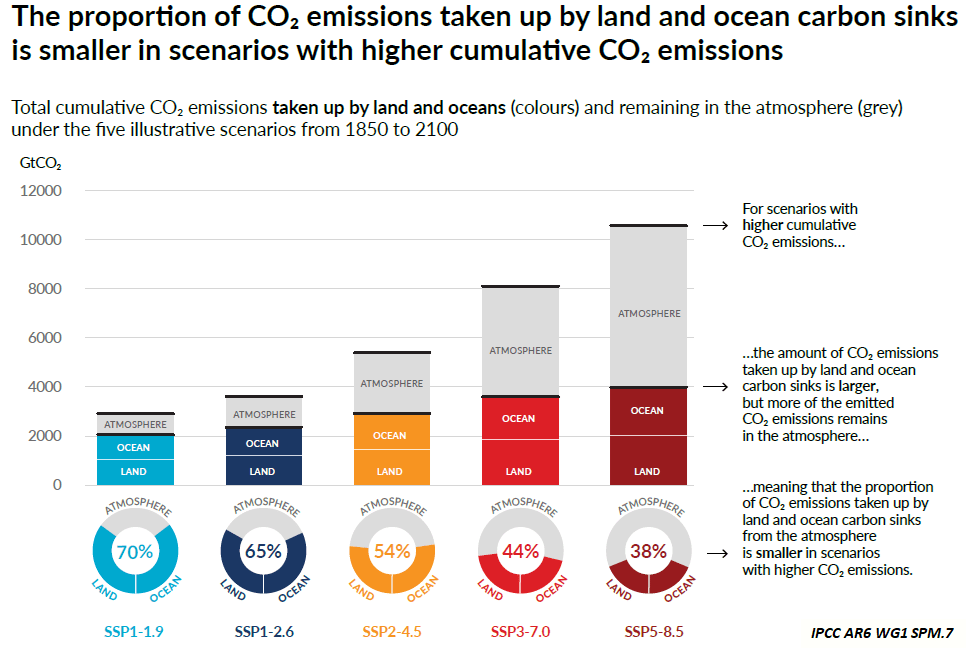

What do models expect from carbon sinks with continuing emissions then? The infographic above shows the overall pattern: in general, Earth’s natural carbon sinks will likely keep on taking up carbon in to the future, with more taken up the more humans emit. However, the final proportion of the carbon emissions taken up declines the further warming goes – while 70% gets taken up under the very low emission scenario (higher than the current 52% as some more gets taken up after net-zero is reached), only 54% is taken up in the medium emissions scenario we’re currently tracking, and only 38% of emissions would be taken up in the extreme emissions scenario.

This means that the warmer it gets, the more CO₂ stays in the atmosphere, causing more warming. This is because models suggest that carbon sinks will increasingly struggle with further climate change. In the ocean, less CO₂ can dissolve in warmer water, while ocean acidification changes the balance of dissolved carbon in a way that slows down further CO₂ drawdown. On land, while CO₂ is “plant food” that boosts growth and carbon uptake, shifting rainfall patterns and increasing extremes are also stressing and killing plants, limiting the extent to which they can benefit from increasing CO₂.

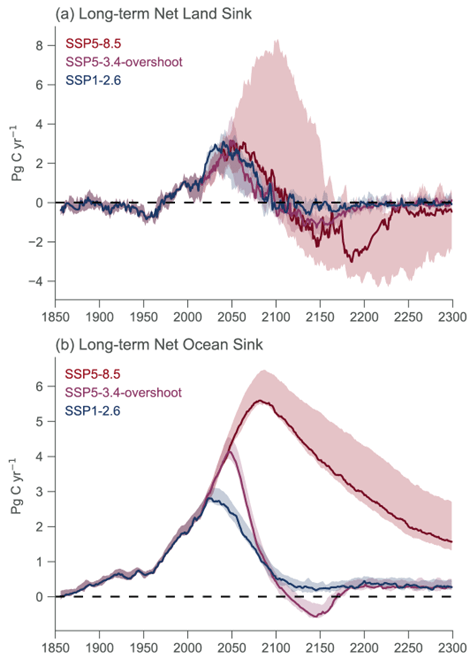

In Earth system models, the end result shown in the plots below is that the land sink peaks around 2050 for both low and extreme emission scenarios, as while the latter has more CO₂ to fertilise plants they also get hit hard by further climate change. Eventually, the climate feedbacks on the land sink are so bad in this scenario that it transitions to being a large carbon source after 2100. (Incidentally, and contrary to some papers’ framings, such a sink-to-source transition at either regional or global scales is not technically a tipping point by the common self-sustaining state shift definition, as if warming were to fall then in most cases land would switch back to being a net sink).

There’s a lot of uncertainty on these projections though – some models project a much higher peak, while others decline much sooner. In contrast, the ocean carbon sink has somewhat less uncertainty, with the sink increasing with higher emissions, continuing to take up some CO₂ even under extreme emissions, and only shifting to being a net source if massive carbon dioxide removal drives a big drop in atmospheric CO₂.

An issue with these projections is that both land and ocean parts of models are lacking important details and processes, which may mean future carbon sink capacity is over-estimated. For example, land vegetation models don’t represent the effect of extreme events on plant mortality well, or where low nutrient soil limits CO₂ fertilisation. Ocean models meanwhile mostly don’t resolve the smaller scale eddies needed to better represent ocean circulation changes, which could have a big impact on how much carbon can be sequestered for the long-term in the deep ocean.

On the other hand, improving other model processes can lead to a more robust land sink, and warming’s impact on the ocean’s ‘biological pump’ of carbon to deep water is complex. And while models struggle with extremes, they do feature enough key processes and feedbacks to capture past trends fairly well. However, given some observations of earlier-than-expected land sink decline, we should not assume carbon sinks will follow current model average projections.

Overall, while we know models may be under-estimating carbon sink decline, we don’t have evidence yet from either models or observations supporting a future collapse rather than more gradual decline. We also don’t know how the sinks would respond if 2023-24 turns out to be some kind of climate system shift, with an abrupt step up in warming likely to correspond with an abrupt increase in ecosystem stress. What we can say though is that the more CO₂ is emitted and climate change unfolds, the more Earth’s natural carbon sinks will struggle, making it even more critical to reduce emissions as rapidly as possible while carbon sinks are still drawing down CO₂.

Summary

2023 was a bad year for the land carbon sink, mainly driven by a strong El Niño causing widespread droughts and wildfires. But such bad years aren’t so unusual – over past decades there have been multiple years with low land carbon uptake, often associated with El Niño events too. When smoothing out the low and high years, the land sink has remained remarkably stable over the long term, with around one third of total human CO₂ emissions being taken up by land ecosystems.

Despite this trend, we expect the land sink to start struggling at some point, possibly sooner than models currently project, and we can’t rule out that 2023-24’s climate records may mark a turning point. However, we’ve not yet seen sign of this at the global scale, with regrowing forests so far taking up the slack as the Amazon and boreal forests have struggled. The global land sink will start to take up less CO₂ at some point though, meaning each tonne emitted will cause proportionally more warming. This means we can’t assume carbon sinks will comfortably buffer human emissions indefinitely, making it critical to cut emissions now to help keep carbon sinks going strong.

~

This post was written by Dr. David Armstrong McKay, a Lecturer in Geography, Climate Change and Society at the University of Sussex, and an Associate at Stockholm Resilience Centre and the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute.

Featured Image: False-colour image captured by the OLI-2 sensor on Landsat 9, showing smoke from understory wildfires burning in densely forested areas south of Manaus in the Brazilian Amazon. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Change log: 3/12/24 – graph added from GCB / Glen Peters to show land sink estimates up to 2023 alongside projected land sink for 2024.